Stories - Carolina Echeverri

COLD LOVE & CORDILLERAS: INTERVIEW WITH CAROLINA ECHEVERRI

After spending 15 years in the music industry, Carolina Echeverri (Denmark/Colombia) opted for the world of photography. Since then, she has been spending her evenings in the darkroom teaching herself to make imperfect prints: hand painted, torn, stacked on top of each other. This resulted in a visual example of time, weather, subject and human emotion edited into a narrative structure.

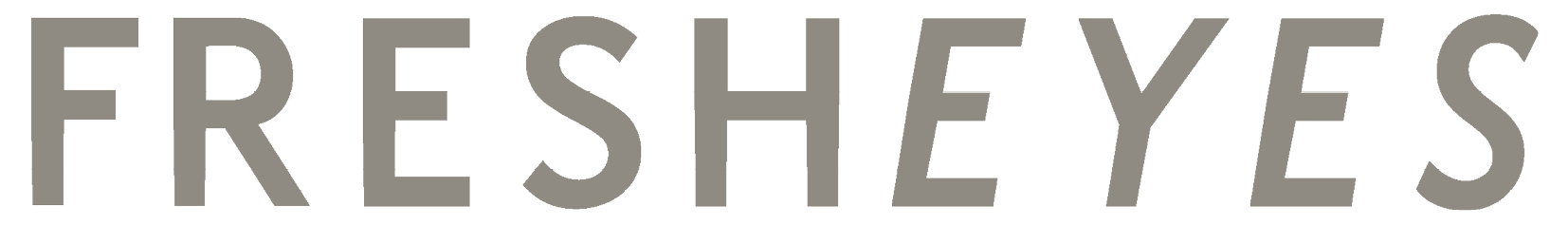

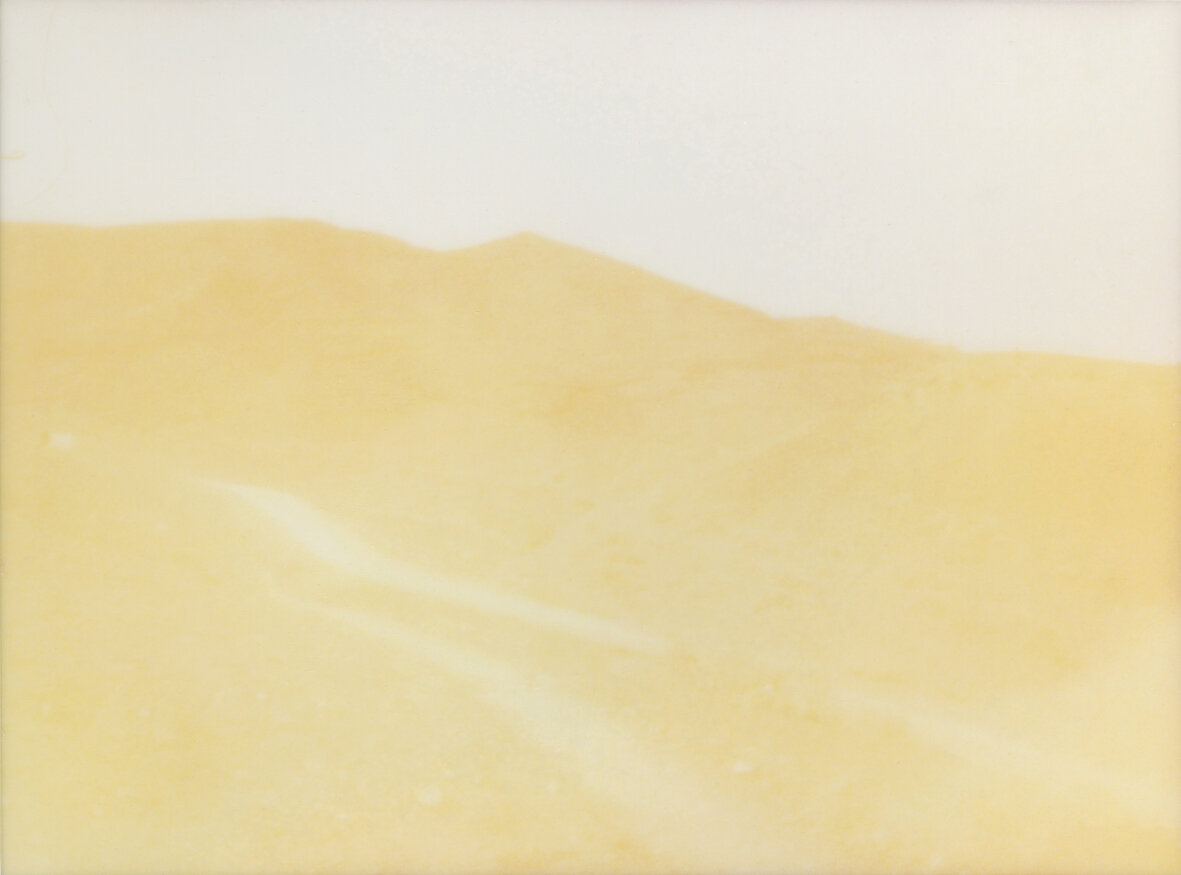

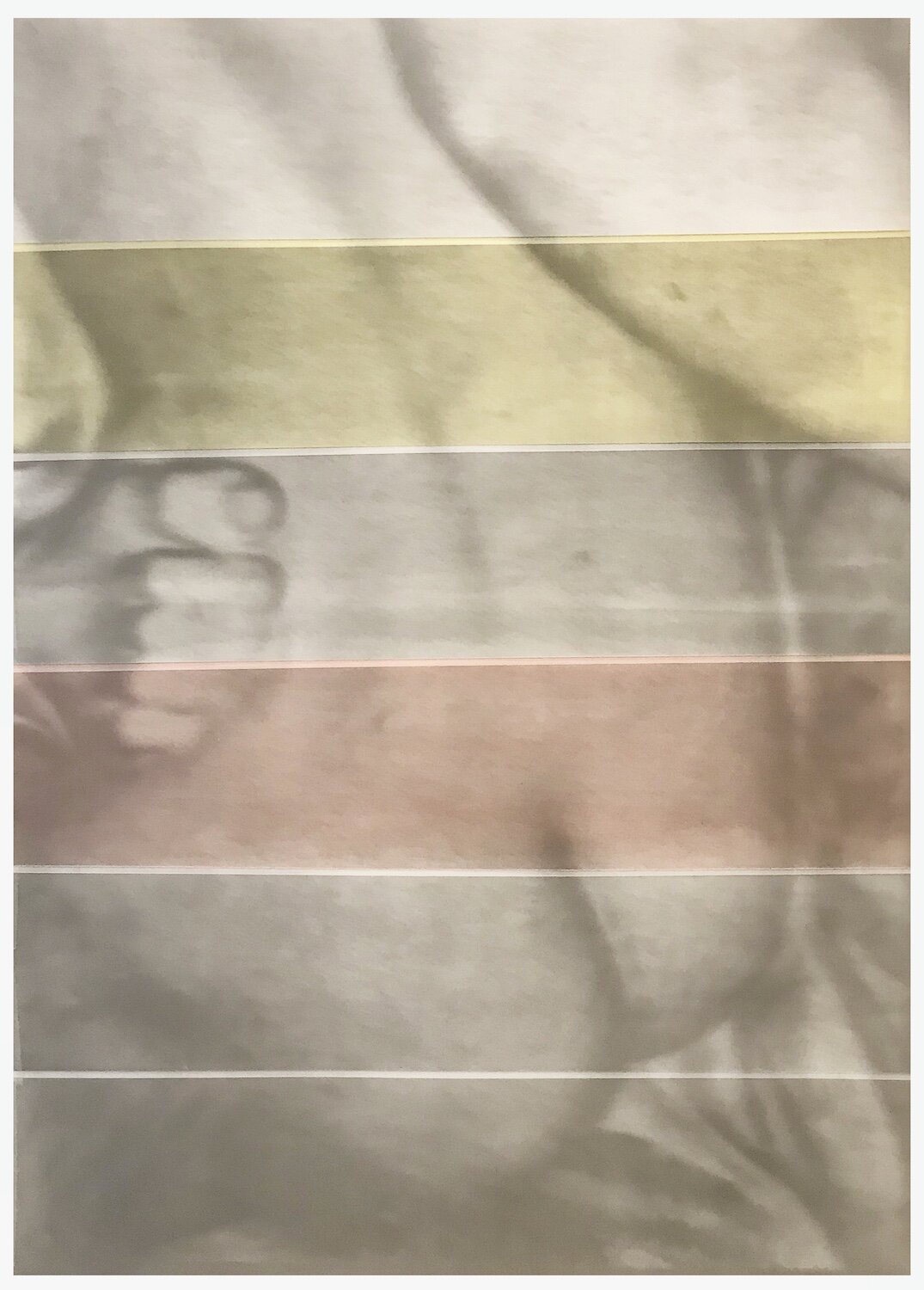

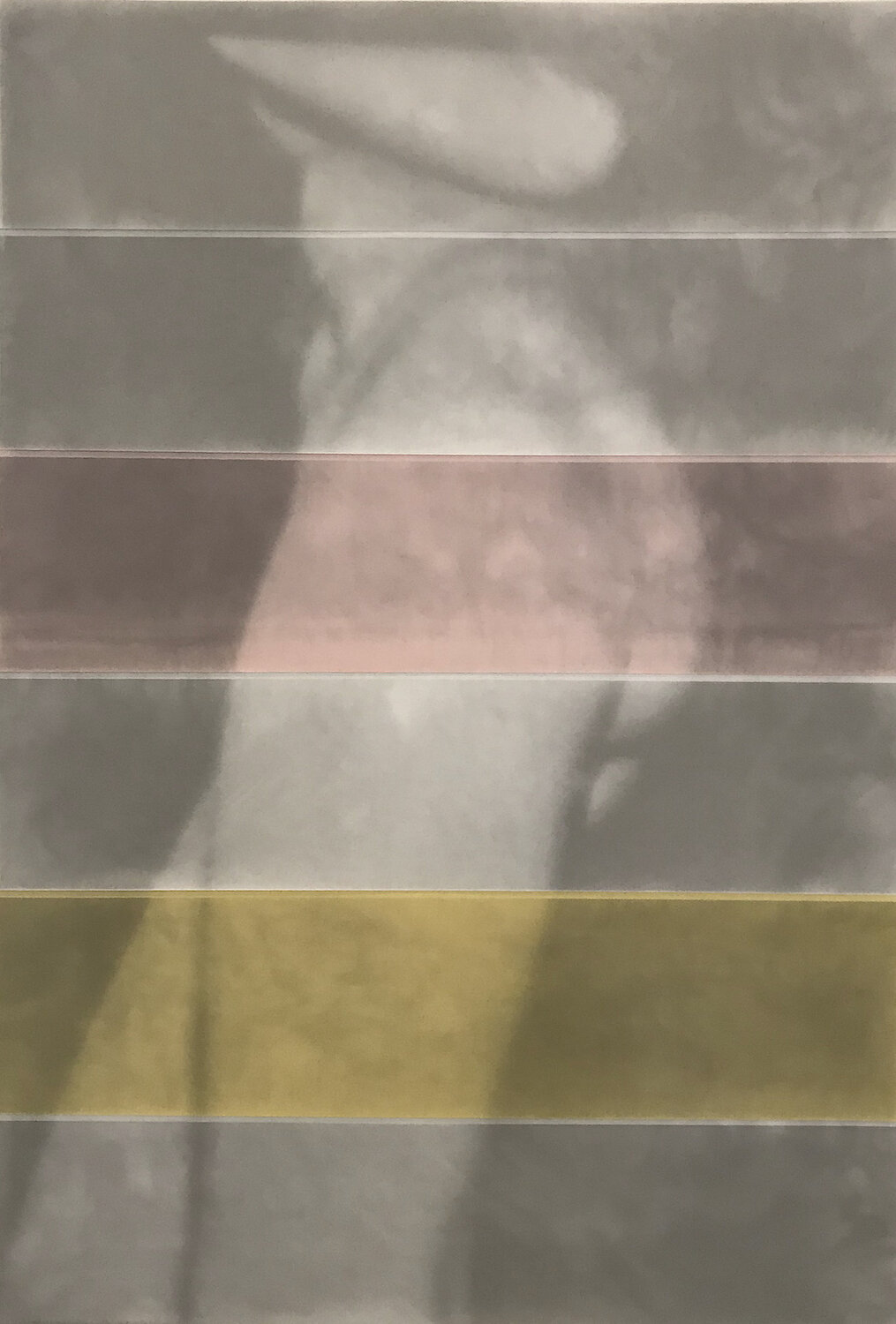

Echeverri grew up in the Colombian “cordilleras” (mountain ranges), surrounded by thousand shades of greens and patters defining her location, time and weather. In ‘Under the Sheets’, she mirrors both the security and danger that the natural beauty represents.

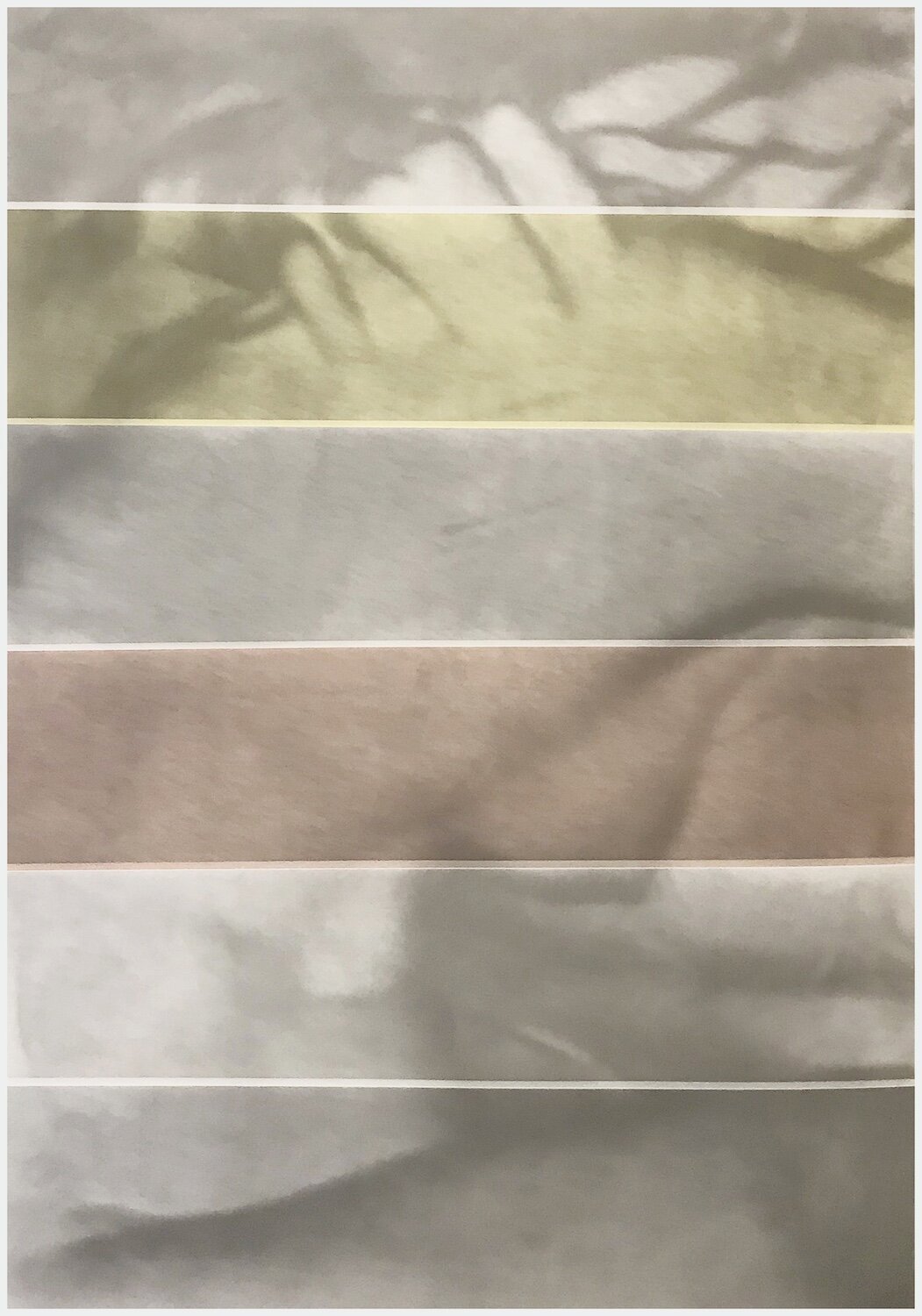

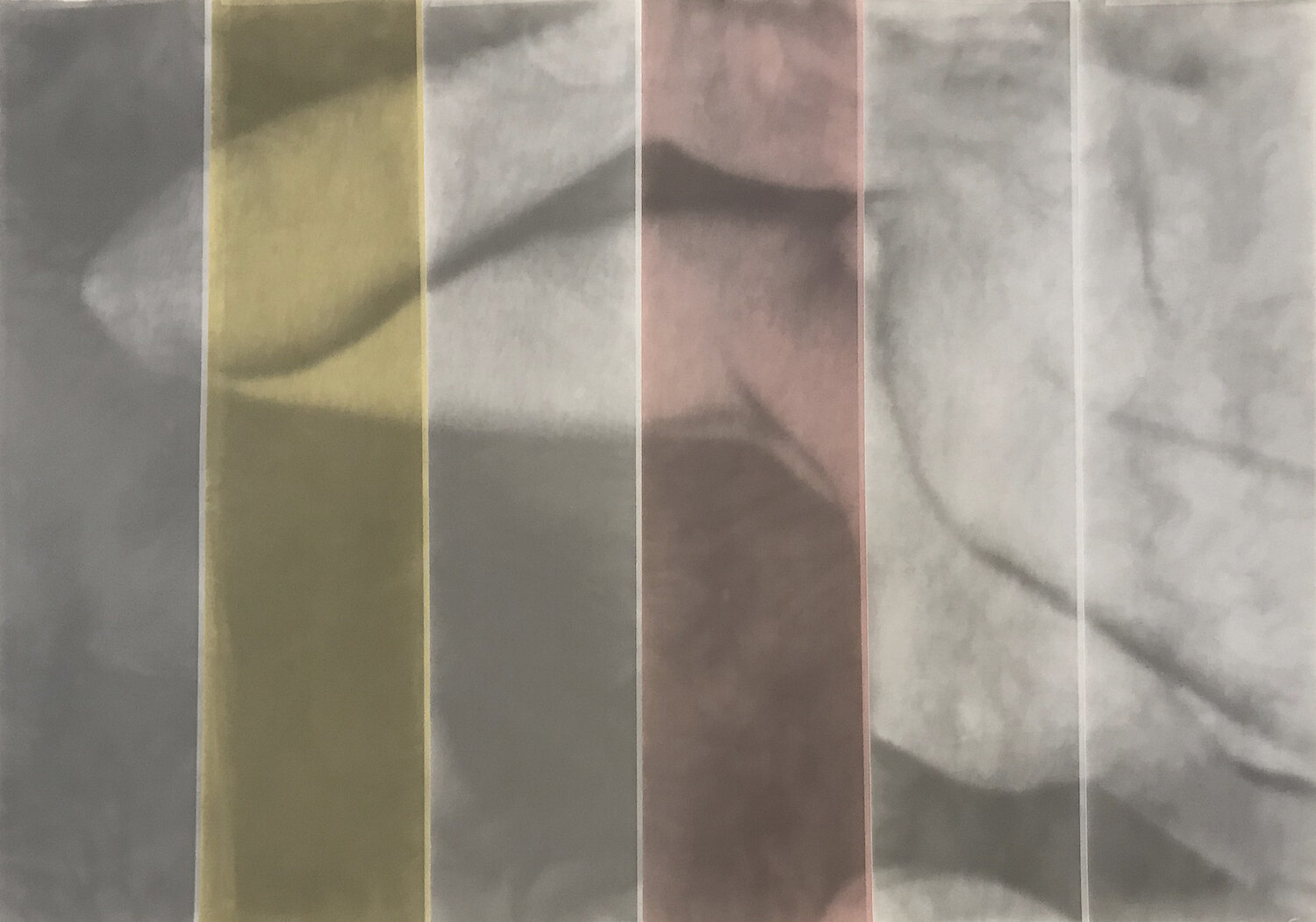

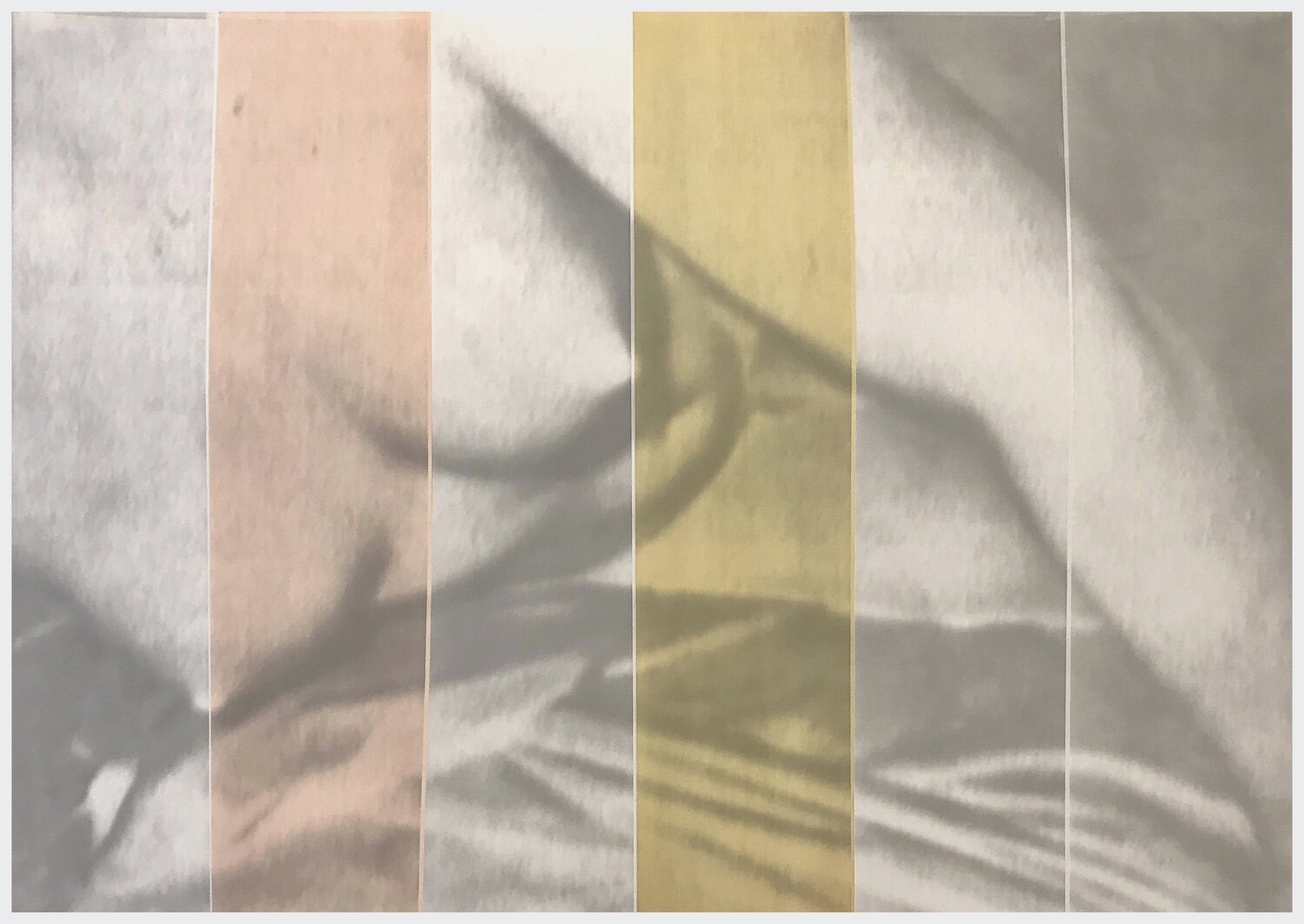

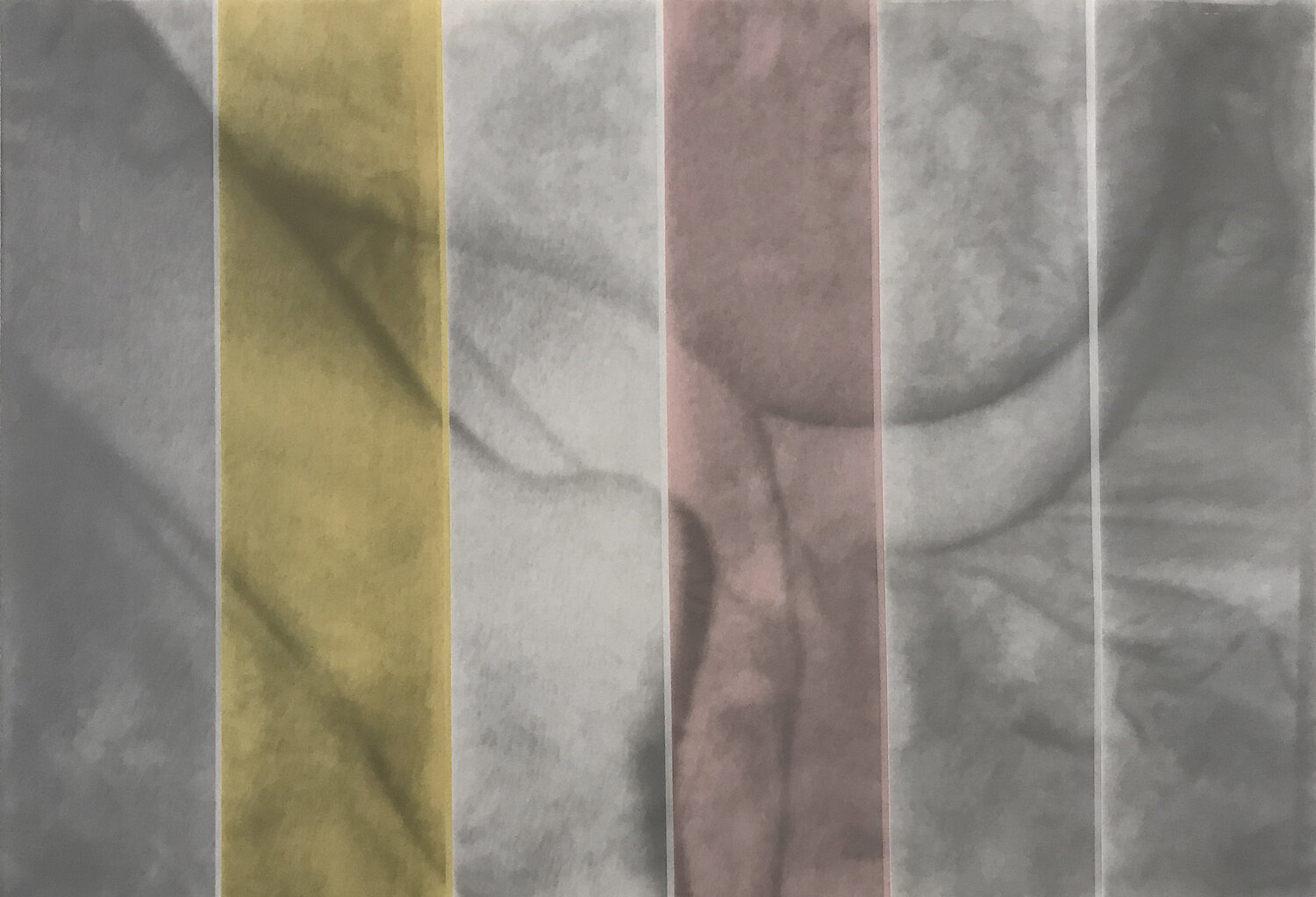

In another project, ‘Cold Love/Rapture’, she reflects on her strict upbringing in the Catholic-Colombian environment. Particularly, the repressed sexuality as locally promoted; the surrounding passion, sensuality and eroticism are considered as a sin in that society.

Your images from the series ‘Under the Sheets’ contain very saturated hues of orange, yellow and pink. What do these colours represent for you? Do they perhaps correspond with your dream-like memories of growing up surrounded by mountain ranges?

It’s funny that you mention the dream-like memories, as when I think about it, it makes total sense, yet I must admit it wasn’t a conscious choice. I was actually aiming at visually representing and bringing through the feeling of warmth in dance with the shapes of the mountains. Mountains, throughout time and cultures, have been linked to the Gods of Creation, of motherhood and the one true source of creation. The shapes also allure protection, and there is quite some literature linking the representation of mountain shapes to that of breasts, connecting to the supernatural, sacred and close relationship between a child and a mother... That closeness, warmth and direct source of life is why I dressed these mountains in these particularly warm and soft colours. The images needed to be intimate, safe and give you the feeling of being cuddled up.

In the series you oppose the emotions of both fear and safety evoked from the “cordilleras”, why such juxtaposition?

It all comes down to pure emotion. We don’t understand the real meaning and value of safety until it’s taken away from us, and when that fear and angst suddenly crawl into us, we can see the vital importance of the things that had kept us safe and protected us before. It’s crucial to experience these feelings and become aware of them.

Truer than ever, in just a matter of weeks, our worldwide health systems are championed, applauded, praised and valued not by a few, but globally because of the protection they are providing to our fragile lives. However, it wasn’t too long ago since those same health systems were slashed in various countries by governments (and those who elected them) moving funds elsewhere. Thereby, we need that juxtaposition, we need that shock to create not only the emotion, the instinct but also the knowledge and value of things that keep us and our humanity guarded, both mentally and physically.

In your other project ‘Cold Love/Rapture’ you reflect on the notion of sin and subsequent closure to the gates of heaven when one’s sexual desires are pursued. How does this conception of entering heaven changed for you throughout the years and after making the series?

I believe the feeling of guilt is directly tied to received reactions from your cultural surroundings in response to different actions you take. Once I moved to Amsterdam and removed the “conservative view and commentary” from the equation, that’s when I could leave my rationale and intuition – be the one setting the tone and the framework of what was important for me as a person.

I learned to love for love’s sake, with my own mistakes, but also without the noise of expectations. It was naked love at its best. And once I learned that, my actions were overall purer, wiser, and the physical aspect of this also changed and elevated me into another plateau of emotion. It’s like graduating in love. And that unrestricted and free love can be one of the biggest human climaxes.

That’s also how the series lives still with me after its creation, it’s there to remind me of human value – to not repeat the mistakes of my upbringing when learning to set rules for my own children. It’s incredibly easy to fall back into memory and tradition. The challenge is to make new traditions with the values that time, and experience have gifted you, and art is standing there visually holding you accountable.

Am I still religious? Yeah, but within a new frame based on the understanding of empathy and love, and by far not driven by the church.

What was your creative process when attempting to aestheticize sin and hence, turn it into something beautiful and pleasurable?

To be honest, it was a messy and rather long process. There is this stunning museum called Glyptoteket here in Copenhagen. One day, I saw there a sculpture by Francois- Raoul Larche called the ‘Meadow and the Brook’. A few years back, I became a mother to a boy, and that sculpture (a woman reaching out to kiss a boy trying to go his own way) grabbed me by the throat. I suddenly faced the feeling of loss – when your child, the most precious of gifts, escapes through your fingers with every passing moment. Since then, I got a bit obsessed with the tangibility and intensity of these sculptures, it was as if they were bearers of truth. So, I bought a few books, studied them and compulsively walked all the rooms every Wednesday.

In my observations, I noticed the strongest or most intense of them were scenes filled with despair, violence and sorrow (Le Paradis Perdu, Perseus slaying Medusa, The First Funeral, etc), which was so contradicting to the beautiful, silky and soft materiality of the stone. Then I suddenly found a love scene, so sensual and fitting, and from there on my eyes were only focusing on spotting and cropping to find the physicality of the characters in all the different scenes in the rooms. I took my FUJI instant and in 30 mins I went around shooting just these close ups of cropped physical scenes.

I scanned the films, made negatives out of them and blew them up into big silver prints. It was important to me to pay homage to the sculptures themselves, their materiality. First, I wanted to soften the images and tones, so I diluted the developer to take away darkness and diminish the contrast. I also wanted the images to feel physical, sculptural, just like their sources, so after trying many things I finally made a collage out of them where the cut parts overlap each other to bring contour and physicality to the work itself. And lastly, the pink and yellow hand painted dyes come once again to represent warmth and intimacy, which was long lost on the complete whiteness of the marble. Every action I took was trying to set the mood into something real, tangible, and extremely sensuous.

Overall, your way of working can be described as destroying the medium while creating something new. Could you please explain to our readers how do you tend to work with photography before you reach your final outcome?

I guess in many ways you are right that it takes a certain level of destruction to create my works, though for me, I don’t feel like it’s destroying the materiality, but more the conception or idea of what the materials are or need to be.

I’m more interested in challenging the traditional idea of photography and trying to bring physicality to it, I want to feel the same when I observe a painting. I want to touch it, I want to be conscious that it’s a palpable work, a human creation and not just a mechanical record or copy of something.

In terms of subjects, I’m rarely going out to find something to shoot, I mostly just shoot what’s around me. In many cases, my inspiration arrives from some sort of self-imposed therapy or way of dealing with demons in my head.

I think it’s rather clear by this point in the interview that I am dominated by the idea of tangible and poetic works, so colour is a vital tool for me. Both in the lack of it, but also when present, it’s always applied by my hands, with either dyes on the actual silver print, or messing up the films with light and temperature to create a surreal and imposed effect. With light, however, I need to be able to relinquish control, making it into a liberating approach which is also rewarding in its playfulness.

The series is scheduled to be exhibited on the occasion of the Copenhagen Photo Festival 2020 in June (fingers crossed).

You can meet Echeverri's work and other 99 great photography talents on FRESH EYES book.